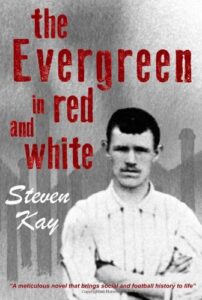

Top Ten Football Books: Steven Kay

Steve’s excellent novel The Evergreen in red and white was published in 2014. It is a fictionalised telling of the true story of Rabbi Howell, the first Romani professional footballer and International player. The novel lifts a lid on the early game and working class life in a northern industrial town and seeks to explain why Rab, a stalwart of the club, was sacked and transferred to Liverpool just weeks before Sheffield United won the English First Division.

Steve’s excellent novel The Evergreen in red and white was published in 2014. It is a fictionalised telling of the true story of Rabbi Howell, the first Romani professional footballer and International player. The novel lifts a lid on the early game and working class life in a northern industrial town and seeks to explain why Rab, a stalwart of the club, was sacked and transferred to Liverpool just weeks before Sheffield United won the English First Division.

In addition to his writing, Steve has since started his own small publishing company: 1889 Books. He blogs about football fiction at: www.stevek1889.blogspot.com/2014/06/football-fiction.html You can follow him on Twitter @SteveK1889

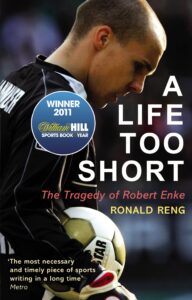

A Life Too Short: The Tragedy of Robert Enke by Ronald Reng

A Life Too Short: The Tragedy of Robert Enke by Ronald Reng

Football is littered with tragic figures: Gascoigne, Fashanu, Speed, and recently Lee Collins. It keeps happening. It shouldn’t. Is there something unique about the game that piles pressure on young men? Probably. Should clubs do more. Definitely. Of course men’s mental health issues are not limited to football, but the game still does not take enough responsibility as it shoves players from very young ages through the sausage machine and (gotta love a mixed metaphor) thinks little of the wreckage it leaves in its wake. Reng, a journalist, befriended Robert Enke and followed his career. He wrote this book after the keeper’s death. It is incredibly well written and is heart-wrenching. You know that it’s not going to be a happy ending, but you still try to will it otherwise. Every football manager, every club chairperson, every administrator should be questioned about this book when they are interviewed for a job. Fans of the game should read it to understand what kind of insanity they have driven the game into becoming.

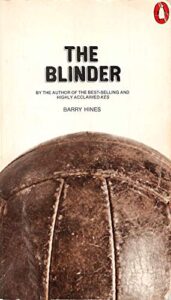

- The Blinder by Barry Hines

Written in 1966, this was Hines’ first novel, and in my opinion his best.

Everything he has written has been eclipsed by the film Kes, even the novel that Kes was based on: A Kestrel for a Knave. But The Blinder is, if anything, more authentic and a more complete novel than A Kestrel for a Knave. Even if it is not better (and it is very hard to compare because the film Kes is so strong visually that it blots out almost all imagery from the text), it is at least equal to it. There is an argument for the characters and dialogue in The Blinder being stronger.

The “Blinder” refers to Lennie Hawk, an 18 year-old with a great talent for football. He is naturally talented (he plays a “blinder”) as well as being feckless and drinking and womanising (ah! the sixties and seventies, those were the days, a skin-full as long as there wasn’t a match the day after, a fag at half time in the changing room, and “dolly birds” in miniskirts – proper footballers! – that was irony, in case anyone has any doubt).

The football is well written, and the treatment of the game feels right:

“Nobody’s right for you are they? Why don’t you run away and find yourself an island somewhere?”

“I’ve found one. It measures a hundred by sixty and they’ve goals at each end.”

“And what about the other twenty-one players?”

“They don’t count. It’s just me, and the ball, and the goal.”

So why has The Blinder been largely overlooked? I believe it is quite simply the cultural prejudice towards football. Any books set in the North have to overcome a massive a barrier to gain acceptance – and even then, can only do so if it stays within certain bounds – A Kestrel for a Knave breached that barrier, perhaps because it contained an animal: like a guide dog being a way to make blind people approachable, and thanks to Ken Loach, whose films managed to gain a certain acceptance as northern eccentricities. I bet it probably wouldn’t even find a publisher in today’s publishing climate.

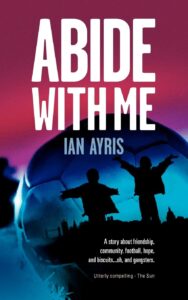

- Abide With Me (and April Skies) by Ian Ayris

It makes me mad that the broadsheets and the literary world rave about a novel like A Natural and overlooked this novel – one with a much stronger story, really important messages about family and belonging, and social breakdown – a novel that is much more skilfully crafted. But perhaps they can’t see beyond their prejudices and the fact that it contains dialect and colloquialisms – and a lot of effing and jeffing – that it was written by someone so obviously working class. It is too easy to dismiss it as soon as they start reading: “There’s things happen in your life what go clean out of your head. They don’t mean nothing see. Most of your life’s like that.” That is not badly written – it is superbly written – you just have to put aside your literary snobbishness and see things for what they are. This novel is carefully crafted prose, without wasted words – every word pulling its weight (possibly with the slight exception of use of the f-word – but there you should see that for what it is – punctuation).

There are some great observations on growing up in the ‘70s and ‘80s and moving accounts of family relationships and the struggles faced by people to make ends meet; a depiction of how easy it is to slip into crime. The plot is also very strong. The football is an important theme – especially in what it says about father-son relationships. It is really nicely integrated into the plot – doing what football does best: providing a metaphor for life.

There are some great observations on growing up in the ‘70s and ‘80s and moving accounts of family relationships and the struggles faced by people to make ends meet; a depiction of how easy it is to slip into crime. The plot is also very strong. The football is an important theme – especially in what it says about father-son relationships. It is really nicely integrated into the plot – doing what football does best: providing a metaphor for life.

The second book April Skies is worth a read but is not quite so strong – suffering the way many sequels to superb works do: how on earth do you follow that. It has a lesser football theme, and a slightly more contrived plot, and is not quite so well crafted.

Papers in the Wind (Papeles en el Viento) by Eduardo Sacheri

Papers in the Wind (Papeles en el Viento) by Eduardo Sacheri

It took me a long time to discover this book – it never came up on search engines for football novels. Given that the game is played with such artistry in places like Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil and given their rich literary heritage, I thought it curious that South America hadn’t produced a great football novel. It turns out it had. The problem is probably the same as why the literary world in this country looks down its nose at the concept of a football novel: why would search engines pick up on such obscure novels, when no one in Islington is vaguely interested in them?

This is a great novel, by any measure. It is well written – the three main characters jump to life. It treats the subject of male friendship and loyalty really well. The two parallel story threads are nicely done. The football backdrop is weighted perfectly – not overdone, but enough to show a passion for the beautiful game and explain its importance without detracting from the story. It is easily one of my favourite football novels.

The translation is not always the best – especially to a British English speaker – I would have enjoyed it more had I not had to keep translating it properly to myself as I went: soccer player = footballer, light tower = floodlight, alternate = substitute, knee-highs(F.F.S.) = socks, cleats = studs, tied and scoreless(!) = nil-nil draw, ‘wall pass’ = one-two, ‘lateral defender’ = Nope, not a clue.

The thing that stops this being totally perfect is the pace of historical story thread doesn’t quite keep up and doesn’t quite exploit all the ideas that come through in that sequence to its fullest. You’ve got to read this though.

The Damned Utd by David Peace

The Damned Utd by David Peace

Still one of the best football novels. It takes a character we all feel we know to some extent, someone everyone over forty owns a part of, and it makes us feel we get to know and understand him better in a way that only fiction can. We add to the character already in our heads through the creative process of reading and through the words that Peace puts on the page for us. Every one of us will read it differently – for me, my reading is tinged with bitterness from every player who went up the M1 to hateful Leeds: Mick Jones, Tony Currie, Alex Sabella, and so on and on. Add to that an admiration for the character I saw on TV and that last match of his when the whole ground, Forest and United fans alike, chanted “There’s only one Brian Clough.” The Clough family hated the book – of course they did: they had a different version of him, the family man not the ‘Cloughie’ we saw and loved.

We think we know the story that the book covers: his too early exit as a player, how he told the Leeds players that they didn’t deserve their medals; we think we know about his drinking, we know his footballing achievements, and yet somehow you still read on wanting to know what happens.

They way Peace writes about football itself is superb: I read this whilst turning over in my mind how to convey the excitement of the game in words for the novel I was formulating. Newspaper match reports never capture the thrill, the atmosphere: how could you do it? David Storey came close in one scene in This Sporting Life (even though that is Rugby League), but Peace’s book was a revelation. It is pacey and exciting and very readable. I make no apology for trying to emulate something of that (and build on it?) in The Evergreen.

Peace’s work is like performance poetry – it works so well when read aloud: you can hear the speech patterns, hear ‘Cloughie’ in the words (even though they are Peace’s not Clough’s). All those: “down the corridors, round the corners,” and things like: “I still can’t sleep so I open my eyes again; I am still in my modern luxury hotel bed in my modern luxury hotel room, with an old-fashioned hangover and an old-fashioned headache, my modern luxury phone ringing and ringing and ringing –”

Lots of people tell me: “Oh, yes, good film, but, no, not read the book” – which is a great shame: letting all those images be created for you by someone else rather than in your own head.

It is a book that will still be read in a hundred years’ time.

-

English book cover In the Crowd by Laurent Mauvignier (translation by Shaun Whiteside)

Dans la Foule/In the Crowd shows the power of fiction – it takes the reader inexorably towards the events of the 29 May 1985 in Brussels when 39 people were killed and explores the thoughts and feelings of fans caught up in Section Z as well as getting convincingly close to the mentality of a Liverpool fan who was swept up in the crowd, running at those trapped in Section Z. I was struck by the ‘us’ and ‘them’ in the book. ‘Us’ being the French, Italians and Belgians – their common shared perspective and the otherness of the Liverpool fans. This book, written by a Frenchman, holds up a mirror: one of the powerful things in reading the book as a British person is seeing how this event is viewed from a continental European perspective. I spent some time in France in 1985-86 and felt accepted, but I remember the hostility towards a group of us England fans during the World Cup from people who didn’t know us, and the concern on some people’s faces at even our relatively understated support for our team: I felt that ‘otherness.’ The very fact of Faber’s glammed-up British cover, rather than a design more akin to the sober French one also tells us something.

Heysel is a difficult subject, and one we never really faced up to: not properly. This is a sobering read. It could be life-changing. Sadly, most football fans will never read it, or will find it too challenging even if they were ever to pick it up. There is something very dark at the heart of football that books like this force you to reflect on. There are many pages given over to the grief of one of the characters and shock faced by two others: how could it be otherwise and deal with this story properly? However, it is well written and there is ultimately some hope of healing. It requires a fair amount of concentration, so it is not one for flitting in an out of, or when there are distractions.

It is one of those books that takes a while for you to get used to the style of writing: there is a lot of stream of consciousness and also the language is not easy. It suffers a little from translation from the French – no matter how good a translation you have to lose a little meaning or a little fluency. So you have to forgive what seems at times a bit of clunkiness. For example, the idiom for drunk: “rond come une queue de pelle” which translates literally as “round as a the handle of a shovel” gets translated for some reason as the non-existent “pissed as a parrot” which just makes you think “what the ..?” when “rolling drunk” would have done just fine. On the same page there is also a peculiar translation: “désosseur de vielles voitures” becomes: “scrapyard bone collector” which is just weird: “vehicle dismantler” makes better sense. It is particularly problematic when the meaning of the author is a bit surreal in the first place. Anyway, if you can be a little forgiving, as the book goes on you do adjust and gloss over these quibbles. (I guess the answer is to read it in French if your French is more fluent than mine.)

The Thistle and the Grail by Robin Jenkins

The Thistle and the Grail by Robin Jenkins

Published in 1954, this is one of the first football novels. Set in a Scottish town called Drumsagart, somewhere in the Lanarkshire, it follows Andrew Rutherford and his obsession with Drumsagart Thistle in a Scottish lower league. Rutherford has troubled relationships with all around him and seeks solidity, a point of reference, through the Thistle – the team he is president of. It goes to the very heart of why football means so much to so many people: a focus in life, an escape, something outside mundane reality, something to make people feel alive.

There are wonderful, rich, characters and some superb writing. Don’t expect a ‘Roy of the Rovers’ big-kids story from this – it is a good read but is fiction for grown-ups – a novel that makes you reflect on life, makes you think, and which you come away from having learnt something.

Jenkins writes about football beautifully. If Peace captures the pace and excitement, Jenkins captures the emotion and beauty of the game. How about this: “The ball flew like hawk, skimmed the grass like hare, bounced like kangaroo; it had in it not mere air but the hopes, fears, frenzies, and ecstasies of that great crowd. It went everywhere – up on to the terracing even, into the grandstand, into this, that and every section of the field – everywhere except into one or other of the goals.”

I don’t need to say more. Read it for yourself. Judge for yourself.

The Hollow Ball by Sam Hanna Bell

The Hollow Ball by Sam Hanna Bell

I can’t believe it took me so long to find this novel, published in 1961; I am now 53 novels in to this undertaking and this is one of the best. As with all the best in this genre it is not the football itself that makes the book but the mirror it holds up to life, as with any great fiction; in this case the life of a working class, protestant community in Belfast in the 1930s and the experience of a young lad, Davie Minnis, growing up. Football is his ticket out of a narrow life of strict rules, and routines at a textiles warehouse.

The characters are well drawn, and the location and atmosphere are convincing – it is one of those books where you feel immersed in another world: the streets and homes. Minnis himself is interesting, a flawed individual, believable in his self-centredness – ordinary in many ways, so that you can both root for him and respect him, and yet still dislike him for certain decisions and how he treats people.

There are occasional flaws in the writing but a lot of it is beautifully crafted. The following smacked me in the face within a few pages of each other:

“There was a tingle in the air that pierced their hands and turned their laughter to smoke.” So simple and economical a way to express it.

“The streets looked as drab as they did on any other winter morning. He knew at what corners the wind from the snow-covered hills swirled and plucked and where it thrust as inexorably as a shaft of cold metal, and he clutched his hat and poised his body accordingly.”

Match of Death by James Riordan

Match of Death by James Riordan

Vladimir Gretchko is a 15-year-old, junior player for Dinamo Kiev with a great footballing future ahead of him – and then Germany invade, and his future is ripped away from him. This is a superb story, told simply, but well, and being novella length (about 40,000 words) you have no excuse for not reading it. You will get more out of 2 or 3 hours spent with this than scores of wasted hours watching box sets of American series shown on Sky.

It is grim in places but then how do you tell the story of what did Germans did in Ukraine after invasion in 1941? As Jews are deported they are brought to the Dinamo Kiev Stadium: “It was all so orderly, like a school playground when the whistle blows. But where had so many Jews come from? It seemed as if the entire population of Kiev had turned out, claiming to be Jewish. By midday we had a bigger crowd been the first team usually enjoyed!” There are accounts of Nazi brutality that probably give this a 15 rating.

The “match of death” in the title is apparently a match that actually took place in August 1942 between a Kiev team and the Germans and, there is no spoiler in saying, the Kiev team were told they had a choice: “win – you die, lose – you live.” According to the story, this is on orders from Hitler himself – it not being possible for propaganda purposes for the Germans ever to be seen to lose.

Riordan clearly knows his stuff and the account has a very authentic feel, right down to things like details of the kinds of weapons available to partisans. It is economically written; there are no elaborate descriptions which some modern readers seem to shun, but still enough to set a mood in places: “It was one of those wild nights in early October when the wind was high, driving swirling grey-blue clouds across the heavens. The clouds would bare the bright moon for a fleeting second, like a searchlight flitting across the land, back and forth.”

The only fault in the book is perhaps the scenes involving Stalin and Hitler. The author was clearly looking for a way to provide the bigger picture, but, that zooming out from the real story, jars and breaks the flow. It is a difficult one – perhaps the same overview could have been provided with a lighter touch in another way.

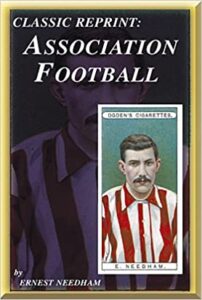

Association Football by Ernest Needham (Classic Reprint Series)

Association Football by Ernest Needham (Classic Reprint Series)

Ernest Needham, an ex-miner, was one of the first working class, professional players to captain England – quite an achievement in the days when the FA was even more dominated by the upper-classes than in the modern era. He was arguably Sheffield United’s greatest ever player captaining them as champions of the English First Division, and to two FA Cup wins. In this short book, written at his height in 1901, he reflects on the game as it was back then and offers advice to aspiring young players – much of which remains very relevant. He was, by today’s cliché, the “consummate professional” and we get a great insight into his character and the history of the game from this book. We lose sight of the game’s heritage to our detriment – Needham would have hated what has become of the modern Premier League and talk of a European Super League.