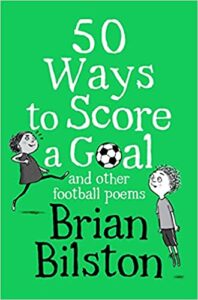

Book Review: 50 Ways to Score a Goal and Other Football Poems by Brian Bilston

Poetry – the bane of many a young adult’s life. Talk of metaphors and metre, consonance and couplets and obscure words, like caesura and onomatopoeia, that never appear anywhere else and seem created just to cause maximum chaos (not least in how you spell them) was enough to send shivers down many a spine and put readers off poetry for life. Even decades on, mention of the dreaded ‘p’ word can bring back palpitations, with sonnets and free verse consigned to one’s schooldays, along with algebra and plimsolls. Wordsworth and Keats may be but distant memories, and gruesome ones at that, so the prospect of a book of poems – even if they are about football – may sound like some kind of modern torture, but I guarantee even if you’ve never enjoyed a single poem in your life and cannot relate to any poet in history, if you’re a football fan, 50 Ways to Score a Goal and Other Football Poems by Brian Bilston will change that.

Poetry – the bane of many a young adult’s life. Talk of metaphors and metre, consonance and couplets and obscure words, like caesura and onomatopoeia, that never appear anywhere else and seem created just to cause maximum chaos (not least in how you spell them) was enough to send shivers down many a spine and put readers off poetry for life. Even decades on, mention of the dreaded ‘p’ word can bring back palpitations, with sonnets and free verse consigned to one’s schooldays, along with algebra and plimsolls. Wordsworth and Keats may be but distant memories, and gruesome ones at that, so the prospect of a book of poems – even if they are about football – may sound like some kind of modern torture, but I guarantee even if you’ve never enjoyed a single poem in your life and cannot relate to any poet in history, if you’re a football fan, 50 Ways to Score a Goal and Other Football Poems by Brian Bilston will change that.

First things first, this book is published by Macmillan Children’s Books and, as such, is apparently aimed at children – but don’t be deceived by that or the lime-green cover. What is so great about Brian Bilston as a poet, and perhaps what separates him from all of those seemingly impenetrable poets of old, is that his poetry is completely accessible – so, yes, children can read and enjoy these poems, but, actually, the references and humour potentially make them even more compelling for adults. There were a couple of poems that I did feel worked specifically for younger readers, but, by and large, adults will enjoy the subtleties and nostalgia of Bilston’s football-themed observations.

The collection of sixty, generally short and succinct, poems is delightfully split into three sections – First Half, Half-Time and Second-Half. And the poems themselves vary greatly in terms of their style and voice, but all with football at their core and all unquestionably accessible. Indeed, although Bilston is a remarkably clever poet, his greatest strength perhaps is that his poems are clever in a way that includes readers rather than excludes them. You don’t have to have a thesaurus at hand and five degrees to understand and engage with his verse, and yet he stills uses the same poetic techniques of the ‘greats’ and plays around with language and form in inventive and exciting ways. His poetry on the surface seems uncomplicated and playful, which makes it fun for readers young and old, but there is so much more going on, though, crucially, it never distracts or belittles the reader. There isn’t that sense of pomp or pageantry that perhaps can make poetry feel alien, nor bombast or floweriness that can unnecessarily obscure – Bilston’s poems, like football itself, are intended to be universal and inclusive.

That is not to say, though, that his poetry is not intricate and elaborate – far from it. Bilston is a master craftsman of poems. Indeed, across this collection, there are quatrains, haikus, acrostic poems and concrete poems, if you want to get technical, and all of them perfectly wrought, but the brilliance of Bilston is that concepts and terminology such as these, which can bewilder, and even intimidate, readers, are demystified and nullified by poems which make the experience fun and engaging. ‘The Thing About Wingers’, for instance, is the perfect example of a concrete poem – essentially a poem whose layout on the page creates a shape or pattern that matches the subject – but there is no need to know this to enjoy it, and the poem itself makes the whole process accessible. And similarly, although titles like, ‘Football Haikus: Starting XI’ and ‘Acrostic Town FC: Matchday Squad’, may conjure images of obscure poetic techniques, Bilston’s poems with their mix of linguistic humour and formal transparency ensure readers’ understanding and engagement. There is never any pretension or prohibition to these poems; even when they are doing the most elaborate and technical of tricks, they remain coherent and inclusive. And whilst humour is central to a lot of these poems and is something that will connect with football fans, there are also a number of more sentimental and poignant poems as well. But, again, rather than cloying and trite, these are perfectly pitched with brilliantly relatable themes, and I defy anyone not to be moved by ‘Kit’ and ‘Every Day is Like a Cup Final’.

The poems cover everything from that routine of picking teams in a playground, the types of goal it’s possible to score, sitting on the subs bench, the unique matchday experience, football sticker collections, the life cycle of a manager, supporting a local team and the trusty lucky bobble hat. Thrown in are really playful poems, including ‘An Educated Left Foot’, which puns on that old football cliché, ‘A Shaggy Dog Story’, which gives a dog’s point of view of chasing after a football and ‘A Ball Speaks Out’ which gives a football’s point of view of being kicked about! There are also tongue-in-cheek meditations on some of football’s more questionable aspects, including diving in ‘And the Award Goes to…’, the incredible curative powers of ‘The Magic SpongeTM’, and football cliches. And Bilston even finally answers that age-old debate: Messi or Ronaldo – in a fashion.

Given the book is aimed at children, I particularly loved the inclusivity of the poems, which feature both genders and different communities, in a very natural way. As a young girl growing up, I would have loved to have read ‘Wonderkid’, in which the footballing protagonist is herself a young girl, whilst poems like ‘The Language of Football’ and ‘The Laws of the Game: Playground Edition’ speak on themes of diversity and equality. ‘The Ballad of Dick, Kerr Ladies FC’ is also both an engaging and informative poem, and throughout the collection, Bilston creates a very real sense of football being everyone’s game and everyone being equal.

I’m hard-pressed to choose my favourite poems, because there are so many that I truly adored , so allow me the luxury of noting my ten favourites – and even that is a challenge, but here goes: ‘Pick Me’, ‘Keepie-Uppies’, ‘On The Bench,’ ‘A Suggestion’, ‘Fixtures’, ‘League Table’, ‘A Poem of Two Halves’, ‘Back of the Net’, ‘Kit’ and ‘Every Day is Like A Cup Final’. I love the variety and shifts in the poems, the way the collection moves so seamlessly from the creative and playful to the sincere and heartfelt, but at every turn there is something that football fans can relate to, and I am absolutely sure that every reader will relish at least one of these poems, although I suspect it will be many, many more. And, again, whether you like poetry or traditionally loathe it, I encourage you to give this book a chance and you may be rather surprised. There is nothing taxing or complicated here, just got old football themes delivered in a refreshing way. And I reiterate that though the book is intended for children, or at least marketed as such, this is really an enjoyable read for adults too, and certainly a book that generations can enjoy together. So whether you know a young football fan or are a slightly (!) older one yourself, I highly recommend this brilliant football book, which is also a very successful crash course in poetry. And you may just find by the end of it (or even at the start) that you’re a poetry fan after all, or at least a Brian Bilston fan.

Jade Craddock

(Macmillan Children’s Books; Main Market edition. May 2021. Paperback: 128 pages)

Football is a game often defined by its playing formations, such as 4-4-2, 5-3-1-1 or 4-3-3. But what about 5-7-5? Sounds implausible?

Football is a game often defined by its playing formations, such as 4-4-2, 5-3-1-1 or 4-3-3. But what about 5-7-5? Sounds implausible?