Book Review – Troy Deeney: Redemption: My Story

For me, a great autobiography gives a reader a really authentic, honest insight into the individual and helps them understand that person more. When the subject of the autobiography is particularly complex and nuanced and someone you haven’t necessarily been able to connect with or relate to before, yet you come away from the book with recognition and perspective, that’s all the more telling of a successful autobiography, and in that respect Troy Deeney’s Redemption excels. Deeney is one of those players that is perhaps largely misunderstood, divisive and dismissed for those without a Watford affiliation and, certainly, I would be guilty of being drawn into this narrative, so I was really intrigued to read this book and came away from it with genuine renewed understanding for Deeney.

For me, a great autobiography gives a reader a really authentic, honest insight into the individual and helps them understand that person more. When the subject of the autobiography is particularly complex and nuanced and someone you haven’t necessarily been able to connect with or relate to before, yet you come away from the book with recognition and perspective, that’s all the more telling of a successful autobiography, and in that respect Troy Deeney’s Redemption excels. Deeney is one of those players that is perhaps largely misunderstood, divisive and dismissed for those without a Watford affiliation and, certainly, I would be guilty of being drawn into this narrative, so I was really intrigued to read this book and came away from it with genuine renewed understanding for Deeney.

Across his career, the Birmingham-born striker has developed, or perhaps rather been tagged with, a persona as something of a rogue, a bit of a pest on the pitch and potentially disruptive off it, but as with any antihero story, there is a backdrop to it all, and Deeney’s is more telling than most in helping readers understand the people, places and events that shaped him, not least a tough upbringing after his biological father abandoned him and his mother and a stepfather not without serious flaws entered his life. The circumstances of Deeney’s younger years are truly eye-opening and, I think, do a lot to unravel Deeney’s character and personality, his bravado, his resilience and his tenacity. He speaks without censor about the challenges and adversity of his upbringing but conversely also with love and appreciation and it’s clear that his early years were both troubling and seminal in shaping, and continuing to shape, him.

Indeed, a large proportion of the book is given over to his life pre-football and even when football becomes a greater part of his story, it almost feels secondary in many ways to everything else that has happened. Football autobiographies can sometimes get bogged down in the minutiae of training, matches, dressing-room tales, but having come from where he’s come from, having been through what he’s been through, Deeney’s story is as much as, if not more so, about the journey, rather than the destination. That’s not to say, football is not central to his life, his passion, but it is part of a much bigger and more significant narrative. In many ways, this only makes Deeney’s rise to the footballing heights all the more miraculous and impressive.

He is the first to admit that he wasn’t necessarily the fastest, most skilful, most talented of footballers, but what he lacked in these areas, he made up for in graft, determination and drive. His is very much a success story for the hard-working, the underdog, the strong-willed. There is obviously talent there too, though perhaps underappreciated, but Deeney’s is above all a journey that underpins the argument that hard work pays off, that good things don’t come easy, that you have to make your own luck. This commitment to hard work, to fight against the odds, to battle his way to the top are attributes that have come to define Deeney the footballer as a tenacious, tough, tireless competitor. Qualities that have perhaps often been used against him, especially by opposition fans, yet qualities nonetheless that should be valued, and qualities that clearly stem from a tough start.

Deeney may be a menace on the pitch, he may antagonise and rile up defenders and fans alike, but being on the pitch, working hard to get there, to prove himself, to improve himself, to rise up from the challenges of his birthplace, of his upbringing, is a success story that shouldn’t be underestimated. He has his flaws, don’t we all, but what is so impressive is that he hasn’t allowed them to hold him back. If anything, he has channelled them, made the most of his attributes and compensated through hard work and determination. He refused to be defined by disadvantage, he refused to take the easy route, and that takes incredible conviction and dedication. It is easy to see that Deeney’s story could have been a very different one, if not for football and if not for his dedication to the game, and whether you love him or loathe him, reading his story, knowing his journey, you can’t take away how far he’s come and how much work that’s taken.

Jade Craddock

(Publisher: Cassell. September 2021. Hardcover: 304 pages)

Buy the book here: Troy Deeney

“You imagine most people have forgotten about you already. The impact you had. Forgotten the games you refereed, the big names you kept under control and, on occasion, man-handled.”

“You imagine most people have forgotten about you already. The impact you had. Forgotten the games you refereed, the big names you kept under control and, on occasion, man-handled.”

This is not Steven Penny’s first book looking at football in Yorkshire, as he took a look at the soccer scene in the White Rose county with,

This is not Steven Penny’s first book looking at football in Yorkshire, as he took a look at the soccer scene in the White Rose county with,  What can you say about a book that you read cover to cover in one session? There’s almost no higher praise than that.

What can you say about a book that you read cover to cover in one session? There’s almost no higher praise than that. Football shirt collecting seems to have grown in popularity in recent years with this reflected in the number of books recently published around the subject. These have included amongst other,

Football shirt collecting seems to have grown in popularity in recent years with this reflected in the number of books recently published around the subject. These have included amongst other,  With the advent of the Premier League in England from the 1992/93 season, football was changed forever. This didn’t just relate to events on the pitch, as overtime players and coaches from abroad came in and brought with them better dietary habits, different training methods and tactical knowhow. Off the pitch with the league awash with Sky’s TV revenue and sponsors willing to be associated with this ‘Whole New Ball Game’, business people from across the globe wanted a piece of the action. Suddenly it wasn’t enough to be a millionaire owner to compete, with the result that now Premier League clubs are the possession of billionaires. As a result many fans more than ever feel distant and without influence from the club they support.

With the advent of the Premier League in England from the 1992/93 season, football was changed forever. This didn’t just relate to events on the pitch, as overtime players and coaches from abroad came in and brought with them better dietary habits, different training methods and tactical knowhow. Off the pitch with the league awash with Sky’s TV revenue and sponsors willing to be associated with this ‘Whole New Ball Game’, business people from across the globe wanted a piece of the action. Suddenly it wasn’t enough to be a millionaire owner to compete, with the result that now Premier League clubs are the possession of billionaires. As a result many fans more than ever feel distant and without influence from the club they support. Growing up in the nineties and coming to football in the new millennium, I had the impression – naively – that racism in the beautiful game was a thing of the past, that it was consigned to an era of hooligans and hostility and would nary tarnish the sport again. How wrong, how ignorant, I was. Two decades into that new millennium and football – and society – is still marred by disgusting instances of racism. Who can forget the way three of England’s heroes of summer 2021 were racially vilified after defeat to Italy on penalties in the Euros? When the vitriol spewed out, for many it was shocking; but, sadly, for many others, there was also a degree of inevitability. The real questions over age, experience and game time which should have been central to the analysis of that penalty defeat, as well as a celebration of England’s best tournament since 1966 which should have rounded off the Euros, were lost to racist abuse and discrimination that proved just how endemic racism is in society and, consequently, football. It has never gone away, as John Barnes points out in his book The Uncomfortable Truth About Racism as he spotlights these uncomfortable truths and debunks myths about progress and equality.

Growing up in the nineties and coming to football in the new millennium, I had the impression – naively – that racism in the beautiful game was a thing of the past, that it was consigned to an era of hooligans and hostility and would nary tarnish the sport again. How wrong, how ignorant, I was. Two decades into that new millennium and football – and society – is still marred by disgusting instances of racism. Who can forget the way three of England’s heroes of summer 2021 were racially vilified after defeat to Italy on penalties in the Euros? When the vitriol spewed out, for many it was shocking; but, sadly, for many others, there was also a degree of inevitability. The real questions over age, experience and game time which should have been central to the analysis of that penalty defeat, as well as a celebration of England’s best tournament since 1966 which should have rounded off the Euros, were lost to racist abuse and discrimination that proved just how endemic racism is in society and, consequently, football. It has never gone away, as John Barnes points out in his book The Uncomfortable Truth About Racism as he spotlights these uncomfortable truths and debunks myths about progress and equality. When you think about the movers and shakers in UK sports broadcasting over the years, Channel 4 might not necessarily be the first name that comes to mind. However, this was the station that brought coverage of the NFL to these shores, laying the foundations of a generation that has seen the game gain a real foothold in this country as well as broadcasting sumo wrestling from Japan and kabaddi from India which both enjoyed cult followings. A more familiar sport though hit the screens via Channel 4 when they picked up the live television rights to Italy’s top football division Serie A in the early 1990s. The output consisted of two programmes, Gazzetta Football Italia on Saturday mornings, which contained the highlights of the previous week’s matches and a piece on Italian culture and Sunday afternoon live games (although this came to change in later years).

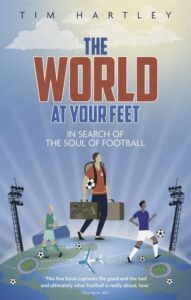

When you think about the movers and shakers in UK sports broadcasting over the years, Channel 4 might not necessarily be the first name that comes to mind. However, this was the station that brought coverage of the NFL to these shores, laying the foundations of a generation that has seen the game gain a real foothold in this country as well as broadcasting sumo wrestling from Japan and kabaddi from India which both enjoyed cult followings. A more familiar sport though hit the screens via Channel 4 when they picked up the live television rights to Italy’s top football division Serie A in the early 1990s. The output consisted of two programmes, Gazzetta Football Italia on Saturday mornings, which contained the highlights of the previous week’s matches and a piece on Italian culture and Sunday afternoon live games (although this came to change in later years). There is within the book a chapter titled, The Football Family, in which the author takes a tongue in cheek look at the range of fans, from the armchair variety concerned only with the Premier League and Champions League to those whose passion is seeking out the most obscure leagues, games and teams from around the globe. As Hartley says, “there’s no single kind of football supporter.”

There is within the book a chapter titled, The Football Family, in which the author takes a tongue in cheek look at the range of fans, from the armchair variety concerned only with the Premier League and Champions League to those whose passion is seeking out the most obscure leagues, games and teams from around the globe. As Hartley says, “there’s no single kind of football supporter.”