Book Review – Into The Bear Pit: The Explosive Autobiography by Craig Whyte

“IBROX, GLASGOW, 7 MAY 2011

“IBROX, GLASGOW, 7 MAY 2011

It was no use. We were stuck. There were fans everywhere, blocking the road.

“Let’s just walk from here, shall we?” I said to the others in the taxi.””

From page vii of Into The Bear Pit, sub-titled, An Explosive Autobiography, it is the first example of Craig Whyte’s leadership. Ironically it would appear, on the evidence of the book, it was his last.

Let me do as we all have to when it comes to matters about the two biggest clubs in Scotland and set out my stall. I am neither a Rangers nor a Celtic fan. I have therefore little investment in the fortunes of either nor in the misery of the other. But I, as a football fan, who saw the benefits of one of the big two fall into the laps and onto the terraces of many a smaller club can see why it is that these two take up so much of our broadcast media and attention. They are a big deal.

On the evidence of his own book, Craig Whyte was very much far from a big deal, though he constantly claims to have handled many big deals. It is his hope that he can make sense of that complexity. He cannot.

The facts are simple.

On or around the 6th of May 2011, Craig Whyte bought Glasgow Rangers Football Club for £1 from Sir David Murray. The deal involved the transfer of considerable debt to Whyte which meant the £1 was symbolic: it was to cost him far more than a quid. In advance of the final transfer of the club, Whyte had been touted by some in the media as a man who had wealth that was off the scale. It was not the last time that the mainstream media was to further suckle on falsely succulent lamb (When buying Rangers, entrepreneur and millionaire, Sir David Murray once hosted a lunch for the Scottish media serving lamb described by one journalist in his column as succulent. Since then it has become the byword for sucking up to owners/directors/anyone in charge). Once in charge, Whyte oversaw the demise of Glasgow Rangers Football Club, which was rapid, and in less than a year it had entered liquidation.

So far, so simple.

What is less clear is how this came about and who were the people who should be held responsible for the fall of Glasgow Rangers. Having been defended by a former director and lawyer of some standing, who spoke warmly to Whyte, of “our club” in court, this is the literary telling of the tale by the singular Craig Whyte.

The picture showing the sale of the club, which is replicated in the book, is perhaps indicative of the whole narrative. It was taken the day after the club was sold but done at the insistence of Sir David Murray. Whyte is seen, hands on hips standing over Murray, casting a shadow over the signing of the papers. The reasoning behind the need for a publicity shot was because, as the Americans might say, the optics mattered on this one. It was not the first time that supporters were to be left hanging in the shadows.

When I bought the book, my hope was that somehow, I could find insight into why the whole thing went wrong from the one man who has cast himself and has been cast as the pantomime villain of the piece: Craig Whyte. Having read the book, I found it to be much more of a Greek tragedy. Perhaps the desire for us to hear and read something revelatory meant that both Whyte and his co-writer, got caught somewhere between the back pages of a red top daily and the front page of The Sun, hoping we would be shocked and appalled sufficiently to avoid noting that it was a tad light on detail and highly opinionated in its approach. The broom of Whyte’s creative focus sweeps long and wide.

The book itself is, however, a compelling read. Hardly likely to end up on the set reading list for any English qualification, it at least manages to hold your attention throughout, though it does tend to rely more on blockbuster statements than demonstratively crafted prose. Unfortunately for the principal character, though if it was designed to restore a fallen man’s reputation it only serves to diminish it further.

There is plenty of evidence of hubris, as he admits that being disqualified as a director, which was someone else’s fault, he sees being struck off as a director as something that: “Anyone with half a brain can get around it and it means the authorities can’t monitor them”. Not being caught out would appear to be a positive in his opinion…

Then came a move to Costa Rica – to avoid paying tax. It is hardly surprising Whyte does not feel responsible for what happened to Rangers as he actually feels responsible for nothing. His views on taxation are pretty clear: “My view on tax is that transactions between people should be voluntary, and that goes for the government as well. Tax havens are completely moral as they stop governments from stealing your money. Governments are basically shakedown operations, like the mafia, but with better manners. They are parasites with no morals whatsoever.” You are left thinking, it takes one…

Whyte was responsible for Rangers ending up in administration. It was an inevitability. He once described the company of which he found himself in charge, as “a basket case” and was the responsibility of the previous regime, not him. He talks about this time thus: “I was in control of the situation. I genuinely believed we could emerge a debt-free club, that I’d still be at the helm, and we could move on. The moment I thought I was in command was precisely the time it all fell apart. Duff and Phelps (the administrators) were acting with HMRC. Suddenly I was an outcast. Duff and Phelps were in charge, and they swiftly instructed everybody not to deal with me.” And so, he was in charge, until he wasn’t in charge. And then they were in charge. Clearly not his fault…

The stuttering form on the pitch, he claims, came through an untested manager, who was gifted to him by the previous board – another fault to be laid at their door.

He goes on to describe being fined by the SFA: “…completely clueless. They were complete clowns. They had a lot to say about me at the time, but did they say anything about the EBT case? A club effectively cheated the game for years and no sanctions were taken against any of the individuals responsible.” The people around him at the time may well have been out to get him apparently as: “It seemed that everyone I came into contact with tried to shaft me. Many of them succeeded.” Not that he ever gave them anything to complain about…

Whyte shows great consistency when he comes to the Rangers’ directors: “I thought the board were a bunch of pompous buffoons and meeting them served no purpose. I decided they were all going to have to go sooner rather than later.” Of the players he shows little by way of self-regard and more of his own self-importance when he speaks of the players thus: “In the main footballers struck me as mercenaries. They were there for the money, not because they loved the club. They got in at 10.30am, had a run around the pitch, got their free breakfast, their free lunch and then they disappeared. What a life.” Even I was tiring of the irony as again it was not his fault…

And then, we come to HMRC. With customary dismissiveness, there is continued self-revelation which seems apparent to those of us who read it but never seemed to be raised by an editor when a man who could not steer the club through this crisis commented that: “From the moment I took over I was confident that we’d either win the case or be able to do a deal with HMRC. At the time of the takeover, I didn’t believe there was a single problem facing the club that was insurmountable. In my experience, when it came to dealing with HMRC, there was always a deal to be done. They always wanted to get paid. It didn’t make sense to me.” He does not go on to outline the deal he was able to make; for he never made one. But then again, they were out to get the Rangers and therefore him: not his fault…

His reputation should be repaired because some big boys did it and then ran away.

Rangers are an institution. One of the major revelations which is a confirmation rather than an expose is that Sir David Murray was able to stop media stories getting out. Whyte inherited that ability as he was able to phone up editors and get them to do his bidding. His downfall was that the internet became the place where the material evidence against him and the previous administration became the stuff of discussion boards and conspiracy theorists. But for once, the conspiracy theorists were accurate. It did not take former player, John Brown standing on a bus outside the Rangers’ Stadium which became known as ‘The Big Hoose’ to suggest that things were dodgy to convince the rest of us that they were. We all knew they were dodgy. That the Scottish press turned on Whyte had as much to do with Whyte not having the recipe to succulent lamb as not being able to hold the line over the greatest story that ought to have been exposed, years before.

And so, it goes on. What he wanted was not, what he was getting. His genius for taking big organisations and turning them profitable seems to have deserted him.

There is irony in abundance as the hope to understand what went on in the club during his tenure is found not in the prose but between the lines. Supporters, long suffering ones, should have welcomed the opportunity to have “the truth” delivered in this book to ease their pain: how disappointed they have been. Whyte gives us insight, but the insight is of a venture capitalist who saw this football club as just another company he needed to turn around, and of a man who cannot see anything in the mirror but a wronged individual, Whyter than Whyte.

But you can hardly put it down.

I struggled to set it aside during my reading of it as each chapter includes stunning revelations that at times made my jaw drop. Not of the deeds done to this unfortunate wee soul who ended up in the court dock, having spent months in the docks of living rooms all over Rangers’ supporters’ Govan homesteads but of the indescribable naivete and lack of acumen, business or otherwise, I have ever read about.

The book itself does a lot to answer questions that non supporters of the club have been asking. Do Rangers have or have Rangers had an undue influence over the Scottish press? Is there sense of entitlement within the club? Are they more establishment than established? The stories of being able to stop stories getting to the press chimes with the experience of journalists like Alex Thompson of Channel 4 who, after years of being safe in war zones, tells tales of being threatened by members of the press in his telling of this sorry tale. The level of arrogance that comes from Whyte is evidence of that sense of who we are rather than what we are. As well as seeing himself as the saviour Whyte tells us as he sees it and castigates everyone bar him. He tells us that there was little by way of a plan to pass over the club to a new owner, little by way of a plan to deal with the debt and nothing in planning for a contingency when the inevitable looked like it was going to happen. Rangers were THE club, THE people and nothing would ever happen to OUR club – just ask the establishment figures behind it, he seems to have thought. The major issue for any fan, of any club, in reading this is that there is little by way of contrition to the people who really do matter – the fans.

The downfall of the club may have been written in the stars, but the meltdown happened through the mind of its principal protagonist.

But why should I care? I do not have an affinity for the club nor a desire for its demise. As a writer I managed to get many column inches out of a saga that I once described as a gift that kept on giving. The media and the pundits had a field day, former players became heroes by supporting one side or another and calling for deeds to be published or making calls to arms to keep the club in existence. Some of the players became Judases in the eyes of sections of the support when they left to play for other clubs when the contracts dried up. If ever the supporter of any club became central to a tall tale, this was it. They were panicked, freaked and judged – often harshly – in their new spotlight.

He does leave a message for Rangers’ long suffering fans: “I don’t care what happens to Rangers now – but I have a lot of sympathy for the Rangers supporters. Those fans have suffered more than anyone, and through no fault of their own.” Once more the irony is that fans DO care what happens to their club and having taken it all away in one hand, his mealy mouthed apology is wiped away again in misunderstanding what he is saying. I am sure the message is meant to go some way to try and stop the death threats and the ill feeling felt towards him. It may never be a big enough pantomime season to ensure his effort to go from the villain to the hero but on the evidence of the book, fans shall be happy to see him recast as one half of the pantomime cow: and not the front end…

By the final page I was left, however, with a deep sense of unease. Of course, this is a self-publicity exercise for a man who was shy of scrutiny, a long letter of self-justification for not being able to turn round the institution he bought and is a long-awaited insight into the Whyte methodology of working. I expected all of that, but it is also revelatory. Rather than it being about Rangers FC and the mess he made, this is a shout out to the world that he was set up and despite all his genius could not make it all good again.

The final visual memory, Whyte left us with, is of a man coming out of a revolving door with a big grin. He had got caught in a revolving door with a policeman, a representative of the authority he despises. As a visual metaphor of his time with Rangers, like how the book began, I can think of no better. We had a man caught in the whirlwind of his own making, who was caught in the clutches of a framework he neither understood nor knew enough about to come out of it with grace. The problem for me is that the supporters of this club are left with his legacy without the ability to admit to his own hamartia, whilst he is sitting somewhere counting what comes from Into The Bear Pit By Craig Whyte, is that he is carrying on his life in some fashion with the scars he left behind a daily living reminder of why he should never have been allowed to get involved in the first place.

Donald C Stewart

(Publisher: Arena Sport. February 2020. Paperback: 240 pages)

Buy the book here: Into the Bear Pit

In recent years, Paul Merson has stuck his head above the parapet to speak openly, honestly, movingly and at times heartbreakingly about his struggles with addiction, and his latest book, Hooked, delves more deeply into these issues, his troublesome relationship with alcohol, drugs and gambling and his long and continuing road to recovery. For all of the brilliance of the man on the pitch, his greatest contribution may be off it, with a book that helps readers understand the illness that is addiction and hopefully speaks to those who really need it.

In recent years, Paul Merson has stuck his head above the parapet to speak openly, honestly, movingly and at times heartbreakingly about his struggles with addiction, and his latest book, Hooked, delves more deeply into these issues, his troublesome relationship with alcohol, drugs and gambling and his long and continuing road to recovery. For all of the brilliance of the man on the pitch, his greatest contribution may be off it, with a book that helps readers understand the illness that is addiction and hopefully speaks to those who really need it. It is a well-known fact that footballers’ careers are relatively short (unless you’re Rivaldo, Sheringham or Paolo Maldini, all of whom played for a remarkable 25 seasons – a whole quarter of a century). So when it comes to hanging up the boots, there is an inevitable and marked void to fill. Unsurprisingly, a number of players have struggled with the transition to post-football life, whilst others kick back and enjoy a well-earned rest. What they don’t do is to decide to take up endurance sport – that is, aside from Francis Benali. And there’s endurance sport and endurance sport. Not satisfied with a ‘simple’ marathon, the former Saints man took on three challenges of truly superhuman effort and all in the name of a good cause. His autobiography, aptly subtitled Football Man to Iron Fran, charts this incredible journey.

It is a well-known fact that footballers’ careers are relatively short (unless you’re Rivaldo, Sheringham or Paolo Maldini, all of whom played for a remarkable 25 seasons – a whole quarter of a century). So when it comes to hanging up the boots, there is an inevitable and marked void to fill. Unsurprisingly, a number of players have struggled with the transition to post-football life, whilst others kick back and enjoy a well-earned rest. What they don’t do is to decide to take up endurance sport – that is, aside from Francis Benali. And there’s endurance sport and endurance sport. Not satisfied with a ‘simple’ marathon, the former Saints man took on three challenges of truly superhuman effort and all in the name of a good cause. His autobiography, aptly subtitled Football Man to Iron Fran, charts this incredible journey. “You imagine most people have forgotten about you already. The impact you had. Forgotten the games you refereed, the big names you kept under control and, on occasion, man-handled.”

“You imagine most people have forgotten about you already. The impact you had. Forgotten the games you refereed, the big names you kept under control and, on occasion, man-handled.” What can you say about a book that you read cover to cover in one session? There’s almost no higher praise than that.

What can you say about a book that you read cover to cover in one session? There’s almost no higher praise than that. Growing up in the nineties and coming to football in the new millennium, I had the impression – naively – that racism in the beautiful game was a thing of the past, that it was consigned to an era of hooligans and hostility and would nary tarnish the sport again. How wrong, how ignorant, I was. Two decades into that new millennium and football – and society – is still marred by disgusting instances of racism. Who can forget the way three of England’s heroes of summer 2021 were racially vilified after defeat to Italy on penalties in the Euros? When the vitriol spewed out, for many it was shocking; but, sadly, for many others, there was also a degree of inevitability. The real questions over age, experience and game time which should have been central to the analysis of that penalty defeat, as well as a celebration of England’s best tournament since 1966 which should have rounded off the Euros, were lost to racist abuse and discrimination that proved just how endemic racism is in society and, consequently, football. It has never gone away, as John Barnes points out in his book The Uncomfortable Truth About Racism as he spotlights these uncomfortable truths and debunks myths about progress and equality.

Growing up in the nineties and coming to football in the new millennium, I had the impression – naively – that racism in the beautiful game was a thing of the past, that it was consigned to an era of hooligans and hostility and would nary tarnish the sport again. How wrong, how ignorant, I was. Two decades into that new millennium and football – and society – is still marred by disgusting instances of racism. Who can forget the way three of England’s heroes of summer 2021 were racially vilified after defeat to Italy on penalties in the Euros? When the vitriol spewed out, for many it was shocking; but, sadly, for many others, there was also a degree of inevitability. The real questions over age, experience and game time which should have been central to the analysis of that penalty defeat, as well as a celebration of England’s best tournament since 1966 which should have rounded off the Euros, were lost to racist abuse and discrimination that proved just how endemic racism is in society and, consequently, football. It has never gone away, as John Barnes points out in his book The Uncomfortable Truth About Racism as he spotlights these uncomfortable truths and debunks myths about progress and equality. When you think about the movers and shakers in UK sports broadcasting over the years, Channel 4 might not necessarily be the first name that comes to mind. However, this was the station that brought coverage of the NFL to these shores, laying the foundations of a generation that has seen the game gain a real foothold in this country as well as broadcasting sumo wrestling from Japan and kabaddi from India which both enjoyed cult followings. A more familiar sport though hit the screens via Channel 4 when they picked up the live television rights to Italy’s top football division Serie A in the early 1990s. The output consisted of two programmes, Gazzetta Football Italia on Saturday mornings, which contained the highlights of the previous week’s matches and a piece on Italian culture and Sunday afternoon live games (although this came to change in later years).

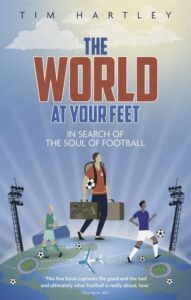

When you think about the movers and shakers in UK sports broadcasting over the years, Channel 4 might not necessarily be the first name that comes to mind. However, this was the station that brought coverage of the NFL to these shores, laying the foundations of a generation that has seen the game gain a real foothold in this country as well as broadcasting sumo wrestling from Japan and kabaddi from India which both enjoyed cult followings. A more familiar sport though hit the screens via Channel 4 when they picked up the live television rights to Italy’s top football division Serie A in the early 1990s. The output consisted of two programmes, Gazzetta Football Italia on Saturday mornings, which contained the highlights of the previous week’s matches and a piece on Italian culture and Sunday afternoon live games (although this came to change in later years). There is within the book a chapter titled, The Football Family, in which the author takes a tongue in cheek look at the range of fans, from the armchair variety concerned only with the Premier League and Champions League to those whose passion is seeking out the most obscure leagues, games and teams from around the globe. As Hartley says, “there’s no single kind of football supporter.”

There is within the book a chapter titled, The Football Family, in which the author takes a tongue in cheek look at the range of fans, from the armchair variety concerned only with the Premier League and Champions League to those whose passion is seeking out the most obscure leagues, games and teams from around the globe. As Hartley says, “there’s no single kind of football supporter.”