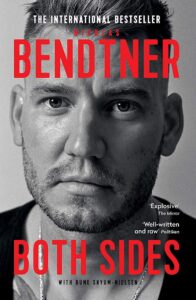

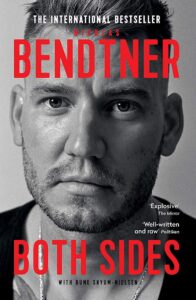

Nicklas Bendtner is perhaps not a major name in Premier League history and certainly not the icon he dreamt, even predicted, he’d become as a young boy head and shoulders above his compatriots in his homeland of Denmark. More of a cult figure, and a problematic one at that, even for Arsenal fans, where he spent the majority of his career, though Bendtner’s name may not be amongst football’s Hollywood elite, his life story is definitely one more suited to the big screen as his autobiography Both Sides makes explicit. Indeed, his early prowess and his move to boyhood club Arsenal which promised much, followed by his larger-than-life antics and headline-making behaviour off the pitch reads like a quintessential Hollywood story of an outsider’s rags-to-riches ascent and eventual fall from grace, with so many outrageous episodes you’d be forgiven for thinking this was a movie script.

Nicklas Bendtner is perhaps not a major name in Premier League history and certainly not the icon he dreamt, even predicted, he’d become as a young boy head and shoulders above his compatriots in his homeland of Denmark. More of a cult figure, and a problematic one at that, even for Arsenal fans, where he spent the majority of his career, though Bendtner’s name may not be amongst football’s Hollywood elite, his life story is definitely one more suited to the big screen as his autobiography Both Sides makes explicit. Indeed, his early prowess and his move to boyhood club Arsenal which promised much, followed by his larger-than-life antics and headline-making behaviour off the pitch reads like a quintessential Hollywood story of an outsider’s rags-to-riches ascent and eventual fall from grace, with so many outrageous episodes you’d be forgiven for thinking this was a movie script.

What makes Bendtner’s story all the more compelling is that the early days promised so much, and that old echo of ‘what if’, ‘what could have been’ sounds loudly in the background of the book. But this isn’t a book of ‘what if’ and Bendtner doesn’t get hung up on feeling sorry for himself, far from it, this is a book about what was, what has been, with Bendtner unflinchingly frank, to the point of blunt, in his assessments of every action on and off the pitch, the good, the bad and the ugly – and, really some of it is very ugly. Yet despite his wild antics and faux pas, Bendtner never comes across as malicious or bad-natured, rebellious, yes, wayward, certainly, headstrong, definitely, but not irredeemable. He is the impish child let loose in a fun fair, and fun he certainly has.

With Rune Skyum-Nielsen, the autobiography hits on a simple but effective formula of breaking down the chapters into various spans of years, which allows everything to be covered but also gives the flexibility to address some periods of Bendtner’s life in lesser detail and some in greater detail as required. This moves the book along nicely at a pace and gives the feeling of leaving nothing unturned. As too, do the details, memories and episodes that Bendtner includes, which are oftentimes genuinely jaw-dropping and eye-opening. Indeed, despite Bendtner’s reputation, which very much precedes him, thanks to several publicised fallings-out, misdemeanours and troubles, he could be forgiven for wanting to brush a lot under the carpet or at least gloss over it. And whilst in the world of social media where Bendtner’s every move has been detailed and every action scrutinised, obviously he wouldn’t have been able to rewrite himself as a saint, but should he have chosen, he could have handled his story very differently, focusing purely on on-the-pitch matters, for instance, to take the spotlight, the heat off everything else. But whatever you think of Bendtner, and opinions do seem very strong, the way he fronts up to even the darkest corners of his past and tackles things like alcohol, gambling, womanising and football culture head on – even if it doesn’t reflect the most positively on him – is unquestionable and his frank, unfiltered voice remarkable. A lot of autobiographies sadly seem sanitised to repair or cement a reputation, whilst others claim to be outspoken and honest. Bendtner’s is certainly not the former and is definitely the latter but in a way that exposes all others as mere child’s play. This isn’t so much warts and all, as warts, spots, lesions, blisters, blemishes – the whole graphic caboodle. I don’t think any other football book I’ve read, at least not in a long while, comes anywhere near close to Bendtner’s scrutiny. So whether you’re a fan or Bendtner or not, know a lot about him or a little, if it’s an unflinchingly honest behind-the-scenes insight into football and all of its trappings you want, this is the book for you.

His on-pitch story is covered well and is interwoven with his off-pitch life nicely, but there is no escaping the fact that it is his off-pitch world that sustains the reader in this book. And that perhaps sadly says it all about Bendtner’s career. Learning the true extent of off-field issues and troubles and his lifestyle makes for a seemingly entertaining read but in many ways it’s also poignant as he confronts betrayals, family breakdowns and trust. Alcohol, gambling and womanising are also central themes, and rather than be contrite or humbled, he is as frank and straightforward as ever. For those thinking the problem days of football were consigned to the past, the book comes as a real wake-up call to the continued issues that dog the sport and its players, particularly those like Bendtner, who seem, be it through quirks of character or personality or genetics, most susceptible.

Whilst Bendtner’s actions, particularly as he gets older, seem reprehensible, again there’s that question of ‘what if?’ hanging over it all, in terms of his early years in football and how perhaps he was handled – or possibly, rather, mishandled. Would a different approach perhaps have led to different results? Would he have continued to rival van Persie and Ibrahimovic as he had done for periods with a different coach, a different club, a different philosophy? And would he have achieved his ‘Golden Boot’ aims if he was given a different outlet off the pitch? Although there is no shying away from the fact that there are a lot of mistakes and misjudgements on Bendtner’s part, and a recognition of his challenges, the book raises the question of how football handles mercurial young talent. Bendtner is not the first, nor will he be the last, young footballer with prodigious potential but also a maverick character, with certain traits and predispositions, and yet football has never seemed to learn how to nurture and care for these individuals, allowing them often to self-destruct. Yes, there has to be a sense of individual responsibility but that comes later on and perhaps we need to ensure the football world does enough in the early stages to protect and steer all of its charges, not only those blessed with self-discipline and attentiveness, and to offer the necessary off-field support needed. Bendtner is clearly no angel, nor I suspect would he ever be or want to be, but it feels like his story wasn’t necessarily inevitable.

The final chapters do point to a changing man, as Bendtner, now 33, finds himself at a very different stage in his life, and possibly a very different reality to that he envisaged when he was ruling the pitches as a youngster in Denmark. However, it’s clear there is still a long way to go, and with retirement yet ahead of him, maybe the hardest part of his journey yet, when football is completely behind him. Sadly, this side of football is also still too often ignored and I imagine Bendtner’s story is replicated the world over, although not quite to the heights he reached. Call me naïve, but I find the ending of the book poignant and can’t help hoping that despite his demons, his bad press, his misadventures and plain bad mistakes, Bendtner finds the sort of peace and stability that seem to have eluded him all his life. Whatever you make of the man, and many I’m sure will find his life story unsavoury and disconcerting, it takes a certain degree of mettle to speak so candidly and to face up to such an errant past. This book is also a warning to young footballers, their parents and their coaches about the very real issues and distractions that remain in and around the game. Football is a game we know and love on the pitch, but off the pitch there is still a murkier side, albeit more concealed these days, and one way or another promising footballers like Bendtner can still get caught out.

Jade Craddock

(Monoray. October 2020. Paperback 346 pages)

When you think about the movers and shakers in UK sports broadcasting over the years, Channel 4 might not necessarily be the first name that comes to mind. However, this was the station that brought coverage of the NFL to these shores, laying the foundations of a generation that has seen the game gain a real foothold in this country as well as broadcasting sumo wrestling from Japan and kabaddi from India which both enjoyed cult followings. A more familiar sport though hit the screens via Channel 4 when they picked up the live television rights to Italy’s top football division Serie A in the early 1990s. The output consisted of two programmes, Gazzetta Football Italia on Saturday mornings, which contained the highlights of the previous week’s matches and a piece on Italian culture and Sunday afternoon live games (although this came to change in later years).

When you think about the movers and shakers in UK sports broadcasting over the years, Channel 4 might not necessarily be the first name that comes to mind. However, this was the station that brought coverage of the NFL to these shores, laying the foundations of a generation that has seen the game gain a real foothold in this country as well as broadcasting sumo wrestling from Japan and kabaddi from India which both enjoyed cult followings. A more familiar sport though hit the screens via Channel 4 when they picked up the live television rights to Italy’s top football division Serie A in the early 1990s. The output consisted of two programmes, Gazzetta Football Italia on Saturday mornings, which contained the highlights of the previous week’s matches and a piece on Italian culture and Sunday afternoon live games (although this came to change in later years). Nicklas Bendtner is perhaps not a major name in Premier League history and certainly not the icon he dreamt, even predicted, he’d become as a young boy head and shoulders above his compatriots in his homeland of Denmark. More of a cult figure, and a problematic one at that, even for Arsenal fans, where he spent the majority of his career, though Bendtner’s name may not be amongst football’s Hollywood elite, his life story is definitely one more suited to the big screen as his autobiography Both Sides makes explicit. Indeed, his early prowess and his move to boyhood club Arsenal which promised much, followed by his larger-than-life antics and headline-making behaviour off the pitch reads like a quintessential Hollywood story of an outsider’s rags-to-riches ascent and eventual fall from grace, with so many outrageous episodes you’d be forgiven for thinking this was a movie script.

Nicklas Bendtner is perhaps not a major name in Premier League history and certainly not the icon he dreamt, even predicted, he’d become as a young boy head and shoulders above his compatriots in his homeland of Denmark. More of a cult figure, and a problematic one at that, even for Arsenal fans, where he spent the majority of his career, though Bendtner’s name may not be amongst football’s Hollywood elite, his life story is definitely one more suited to the big screen as his autobiography Both Sides makes explicit. Indeed, his early prowess and his move to boyhood club Arsenal which promised much, followed by his larger-than-life antics and headline-making behaviour off the pitch reads like a quintessential Hollywood story of an outsider’s rags-to-riches ascent and eventual fall from grace, with so many outrageous episodes you’d be forgiven for thinking this was a movie script. Paul Vaessen was at Arsenal Football Club from 1977/78 until 1982/83. During those six seasons he started in just 27 games first team games, with 14 additional appearances from the bench, scoring 9 goals.

Paul Vaessen was at Arsenal Football Club from 1977/78 until 1982/83. During those six seasons he started in just 27 games first team games, with 14 additional appearances from the bench, scoring 9 goals.