In the modern age football feels like it is at saturation point in terms of coverage. Every detail about a player, manager or club is scrutinised to an infinite degree, so much so that nothing feels new, fresh or indeed inspiring.

In the modern age football feels like it is at saturation point in terms of coverage. Every detail about a player, manager or club is scrutinised to an infinite degree, so much so that nothing feels new, fresh or indeed inspiring.

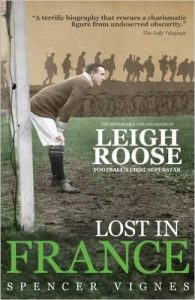

Therefore, it was a joy to read, Lost in France – The Remarkable Life and Death of Leigh Roose, Football’s First Superstar by Spencer Vignes. Here is a story from a very different age, a game in which amateur players still had a place alongside professionals, when football itself looked different to that we watch today and a world unknowingly stumbling towards the First World War.

This is the story of a man described by the author as, “playboy, soldier, scholar and maverick”, and one that had been lost in the annals of time, until now. The book proclaims that Roose was, “football’s first genuine superstar”, and on the evidence presented, it is difficult to argue otherwise.

The reader is treated to tales of Roose’s exploits on and off-the-pitch, where his popularity with the crowds as a player, was matched by that with women up and down the country, including a dalliance with the famous music hall star, Marie Lloyd.

However, to classify Roose as merely a showman and womaniser would be an unfair one, here was a player who was regarded as one of, if not the finest goalkeeper of his era, and went on to play for Wales on 24 occasions, and included amongst his clubs, Stoke City, Everton and Sunderland. Indeed, his style of keeping really was pioneering and has to be the precursor to the way that current custodians such as Manual Neuer the German national goalkeeper, act as a sweeper for his team. Vignes argues justifiably that Roose’s style even instigated a rule change, which in June 1912 saw Law 8 change from, the goalkeeper may, within his own half of the field of play, use his hands, but shall not carry the ball to, the goalkeeper may, within his own penalty area, use his hands, but shall not carry the ball.

It is said that goalkeepers are born not made and have a bravery that outfield players don’t possess. Roose was undoubtedly was one such case, in an era when goalkeepers were not afforded the protection they have today. However, he was not just brave on the field of play and in the later part of the book the author skillfully puts together the story surrounding Roose’s service and subsequent decoration in action during the First World War.

This book maybe only be 192 pages long, but it is an absorbing story of a larger than life character and innovator in the football world and is indeed a poignant and timely tale given that it is 100 years since the Battle of the Somme.

Forget the 24/7 banal and inane coverage of the satellite age of pampered players, sound-bite management and corporate chairman, where the losing of a game is a catastrophe; instead be transported to an era where amateurs played for the love of the game and expenses, and of men who paid the ultimate sacrifice with their lives in the suffering and real tragedy that was the First World War.

In 1914 one of Britain’s most famous sportsmen went off to play his part in the First World War.

In 1914 one of Britain’s most famous sportsmen went off to play his part in the First World War. In the modern age football feels like it is at saturation point in terms of coverage. Every detail about a player, manager or club is scrutinised to an infinite degree, so much so that nothing feels new, fresh or indeed inspiring.

In the modern age football feels like it is at saturation point in terms of coverage. Every detail about a player, manager or club is scrutinised to an infinite degree, so much so that nothing feels new, fresh or indeed inspiring.