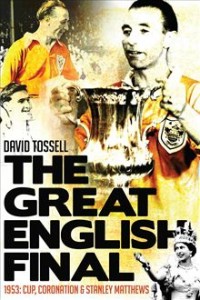

Book Review: The Great English Final – 1953: Cup, Coronation & Stanley Matthews by David Tossell

David Tossell’s book about the 1953 FA Cup Final when Stanley Matthews’ Blackpool beat Bolton 4-3 makes a grandiose but puzzling claim. It says that the “…legendary game continues to occupy a prominent place in English football legend…” (sic) because it has, “…come to represent a Golden Age…” But it doesn’t even leave things at that. Not content with such a mighty claim about the game’s footballing pedigree, it makes wider claims for the match that cannot possibly be substantiated. The raw material for a really good story about football is there all right, but he nearly messes it up by trying to bring in too many different themes. Happily, he is saved by the fact that, finally, the Final delivered.

David Tossell’s book about the 1953 FA Cup Final when Stanley Matthews’ Blackpool beat Bolton 4-3 makes a grandiose but puzzling claim. It says that the “…legendary game continues to occupy a prominent place in English football legend…” (sic) because it has, “…come to represent a Golden Age…” But it doesn’t even leave things at that. Not content with such a mighty claim about the game’s footballing pedigree, it makes wider claims for the match that cannot possibly be substantiated. The raw material for a really good story about football is there all right, but he nearly messes it up by trying to bring in too many different themes. Happily, he is saved by the fact that, finally, the Final delivered.

It is hard to work out exactly why people who want to read about a football match that has come to be known as ‘The Matthews Final’ have to wade through so much that is not actually about the game itself, nor indeed even about football. That is, until you realise that most of the match up to the climactic ending was rather dull. In searching for something more to say about it, Tossell greatly widens his remit to look at the “…merging of historical, cultural and personal narratives…”

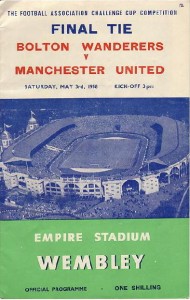

Some of the things he says are pretty much beyond question; the game did take place in Coronation year, Mount Everest was conquered for the first time, it was watched by a much bigger television audience than any previous one, post-War food rationing did stretch out till that year, the Duke of Edinburgh apparently did say the Bolton kit made them look like a bunch of pansies. However he tries, particularly in the first half of the book, to make the 1953 FA Cup Final carry much more weight, culturally, than is fair for what was, after all, a football match. He makes a nod in this direction himself when he says, “…the threat of nuclear obliteration notwithstanding…”

A major problem with the book is its structure. Even before the account begins, we are given pen pictures of the players, curiously called the ‘Cast of Characters’, something that could surely have gone to the back of the book to ease the narrative flow. Except that there is no narrative flow. He repeatedly breaks away from his match report of the Final itself, gleaned from having studied the DVD, to explore his themes. Therefore, his first interlude arrives after a mere seven and a half minutes of uneventful football. He continues to encounter difficulties with this approach until the game itself takes over narrative duties. But before that, we are torn away from our match report yet again, this time to get, er, a match report of the Semi-Final.

Although a little credence can be given to the Final having had some degree of cultural impact since it was watched by so many, it is always dangerous when authors generalise, especially about things like the public attitude to Elizabeth II’s Coronation. People never did and never do act with one mind. Tossell seems much more comfortable and is on much safer and more interesting ground when he talks about the players and supporters. This is, in any case, what most readers of football books want all along. An over-generous helping of social enlightenment is not what they crave.

Isn’t it more real and interesting to read about Stanley Matthews having personalised boots made in Heckmondwike? Isn’t the reader more engaged by the many and varied attempts made by fans to get tickets for the Final? Isn’t everybody happier reading about Blackpool fans presenting a huge stick of rock to Number 10 Downing Street in the days when you could actually walk up to the door and knock?

Once the author has bravely trudged through the historical and cultural narratives, and most of the personal ones, he relaxes much more into what the match itself has to offer and it is amusing to note how he can barely tolerate the legendary commentator, Kenneth Wolstenholme’s commentary of the legendary game. And he teases the reader throughout, being unprepared to admit it was ‘The Matthews Final’. He does have a fair point since Mortensen and Perry made pretty important contributions, too, in actually scoring the goals. Yet the match, in an era when substitutes were not allowed, was turned on its head by Matthews in the final minutes as Bolton tired. They let a 3-1 lead slip and the nation’s most popular player, Matthews, won his medal aged 38. The book’s clanking title ‘The Great English Final’ obstinately launches a counter-claim, but its cover admits the reality. One picture of little Queen Elizabeth, no Everest, no Bolton pansies, but three shots of Stan. 2nd May, 1953 – The Matthews Final.

Review by Graeme Garvey