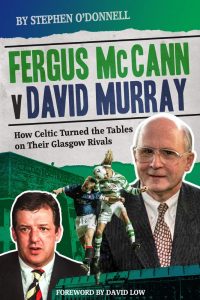

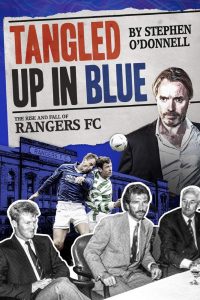

Stephen O’Donnell’s book is a thorough and powerful analysis of how the Glasgow footballing giants – Celtic and Rangers – have been managed and mismanaged. Two ex-Chairmen are the focus of the narrative and it is a damning commentary on how borrowing on a huge scale, mostly prompted by the self-promoting David Murray, was the eventual undoing of Rangers whilst Celtic found an unlikely hero in Fergus McCann. His ‘tight-ship’ budgeting proved unpopular at the time, especially when contrasted with free-spending Rangers, but ultimately proved to be the correct approach.

Stephen O’Donnell’s book is a thorough and powerful analysis of how the Glasgow footballing giants – Celtic and Rangers – have been managed and mismanaged. Two ex-Chairmen are the focus of the narrative and it is a damning commentary on how borrowing on a huge scale, mostly prompted by the self-promoting David Murray, was the eventual undoing of Rangers whilst Celtic found an unlikely hero in Fergus McCann. His ‘tight-ship’ budgeting proved unpopular at the time, especially when contrasted with free-spending Rangers, but ultimately proved to be the correct approach.

Rangers ran up colossal debt and there is a strong sense that they ‘got off light’, not being stripped of the many titles and trophies they won in the years leading up to insolvency in 2012 and not having to start completely from scratch like many smaller Scottish clubs in a similar plight. O’Donnell is also quite clear about who the real culprit is – Sir David Murray, despite Craig Whyte picking up the poisoned chalice as Chairman and then copping for almost all the criticism.

The book, all 353 pages of it, gives a detailed history of both clubs which is essential for a full understanding of the approach and effectiveness of both McCann and Murray. Celtic had a Hiberno-Catholic foundation, unashamedly so since its original existence was directly to help the poor Irish children in the east end of Glasgow. But in Celtic’s case that early sectarianism was continuously diluted over the years. That was not so with Rangers until the time of Graeme Souness as manager and the signing of the Catholic Maurice Johnson in 1989. Much of the blame for this must be directed at the Freemasons who took a firm grip on the club before WW1 when the extreme anti-Catholic stance of the shipbuilding giant Harland and Wolff, major financial supporters, was adopted by Rangers.

The author sees Murray’s Thatcherite attitudes to borrowing as the underpinning factor in why Rangers racked up such massive debts – at times approaching £100 million. The Scottish banks were all too happy to indulge him in this high-risk game, though. It seemed that Murray need only make a phone call to his buddy Gavin Masterton who was Managing Director at the Bank of Scotland and a huge loan would be granted in minutes.

Scottish officialdom comes in for the author’s criticism, too. Examples of its longstanding anti-Celtic bias are legion but perhaps the most notorious is when the registration of new signing, Jorge Cadete, was deliberately delayed for nearly six weeks by Chief Executive Jim Farry until after Celtic had played Rangers in the Cup semi-final.

The question may well be asked; How come this situation was so little understood by the wider public?

This brings us to the final strand of O’Donnell’s argument, that the Scottish media was very pro-Rangers. To those not fully acquainted with all the details, the assumption will probably be that both sides were equally guilty of sectarianism but the author points out it was more like 90:10, Rangers being much the worse. Supported by a fawning media, however, any story was almost always skewed in their favour, particularly at Celtic’s expense.

This anti-Catholic sectarianism peddled by the media was a blight which, ultimately, did no one any good and plenty of harm along the way. O’Donnell does not make the same Freemason link with the press as he does with Rangers but the reader can speculate. Consequently, as the author points out, anything McCann did was viewed negatively in the papers whilst Murray remained their Golden Boy, simply above all criticism. O’Donnell also points out that McCann did himself few favours, his dealings with the media being poor, leaving him open to being mocked and pilloried by them. Which he duly was.

Celtic were to have the last laugh, however, and they say he who laughs last, laughs longest. As Rangers were continuing to store up eventual disaster for themselves, McCann’s financial shrewdness and astute investment in rebuilding Parkhead as a fine all-seater stadium, was finally complemented by Martin O’Neill’s canny management allowing Celtic to compete with Rangers on a consistent level. Then Celtic grew whilst Rangers began to implode until, after the financial crash in 2008, their fate was sealed.

O’Donnell does indulge himself from time to time in reportage on Celtic matches. He is clearly a Celt but, wisely, lets the facts speak for themselves. An observation has to be made that, although it is very well-written, the complete absence of graphs, charts, tables or whatever means that the reader is required to hold an enormous amount of information in his or her head. Being able to make quick cross-references would have greatly helped.

(Pitch Publishing. July 2020. Hardback 353 pages)

Graeme Garvey

If the wider, football-conscious world is aware of just two things about Scottish football, they are surely as follows: firstly, that there is a virulent rivalry in Glasgow between the city’s two great teams, Rangers and Celtic, based on a religious divide; and secondly, that Rangers recently suffered a catastrophic financial collapse, which ultimately led to the club’s insolvency.

If the wider, football-conscious world is aware of just two things about Scottish football, they are surely as follows: firstly, that there is a virulent rivalry in Glasgow between the city’s two great teams, Rangers and Celtic, based on a religious divide; and secondly, that Rangers recently suffered a catastrophic financial collapse, which ultimately led to the club’s insolvency. Fergus McCann Versus David Murray charts the changing fortunes of Glasgow’s two great footballing rivals as shaped by two business moguls. Both men came to prominence in the 1990s when new methods of governance and finance were taking hold of football.

Fergus McCann Versus David Murray charts the changing fortunes of Glasgow’s two great footballing rivals as shaped by two business moguls. Both men came to prominence in the 1990s when new methods of governance and finance were taking hold of football. Stephen O’Donnell’s book is a thorough and powerful analysis of how the Glasgow footballing giants – Celtic and Rangers – have been managed and mismanaged. Two ex-Chairmen are the focus of the narrative and it is a damning commentary on how borrowing on a huge scale, mostly prompted by the self-promoting David Murray, was the eventual undoing of Rangers whilst Celtic found an unlikely hero in Fergus McCann. His ‘tight-ship’ budgeting proved unpopular at the time, especially when contrasted with free-spending Rangers, but ultimately proved to be the correct approach.

Stephen O’Donnell’s book is a thorough and powerful analysis of how the Glasgow footballing giants – Celtic and Rangers – have been managed and mismanaged. Two ex-Chairmen are the focus of the narrative and it is a damning commentary on how borrowing on a huge scale, mostly prompted by the self-promoting David Murray, was the eventual undoing of Rangers whilst Celtic found an unlikely hero in Fergus McCann. His ‘tight-ship’ budgeting proved unpopular at the time, especially when contrasted with free-spending Rangers, but ultimately proved to be the correct approach.

Scotball is Stephen O’Donnell’s second novel following on from

Scotball is Stephen O’Donnell’s second novel following on from